Source: Images and content by A Collected Man @ ACollectedMan.com. See the original article here - https://www.acollectedman.com/blogs/journal/andy-warhol-collector

https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0606/5325/articles/banner_60c329cf-0480-4f9a-a573-e27a01993a09_1024x1024.jpg?v=1628596086

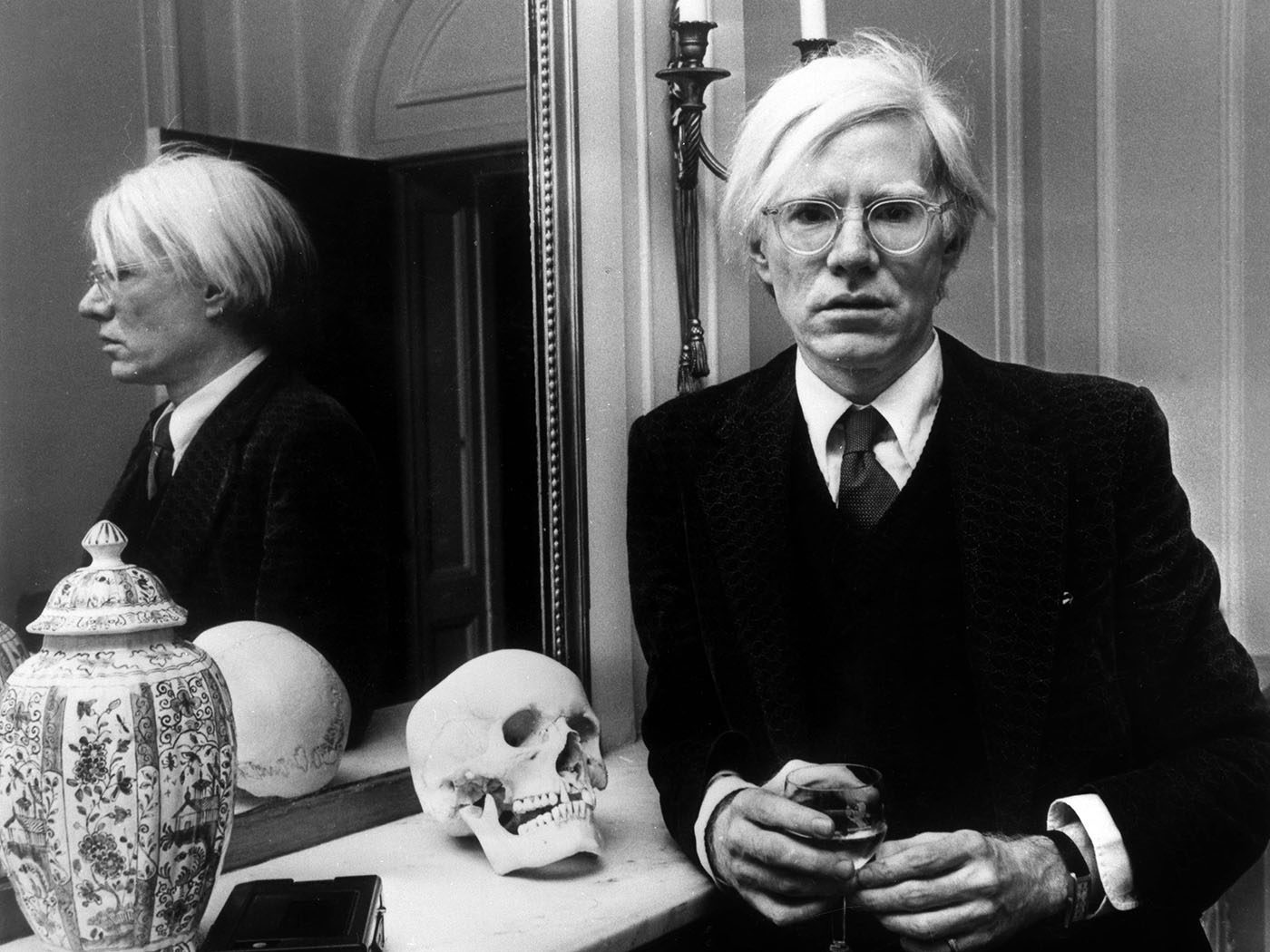

Known as one of the most prolific artists of the 20th century, Andy Warhol’s creative spirit was matched only by his voracious collecting. As it became abundantly clear at his estate sale in 1988, his mindset when it came to acquiring objects was almost unparalleled. Those in the watch community will be aware of Warhol’s affection for the Cartier Tank, but they may have missed the fact that he managed to collect some 313 watches by the time he passed, all of which have gone up for auction. Despite their numbers, very few of these have come back to the open market since they first emerged.

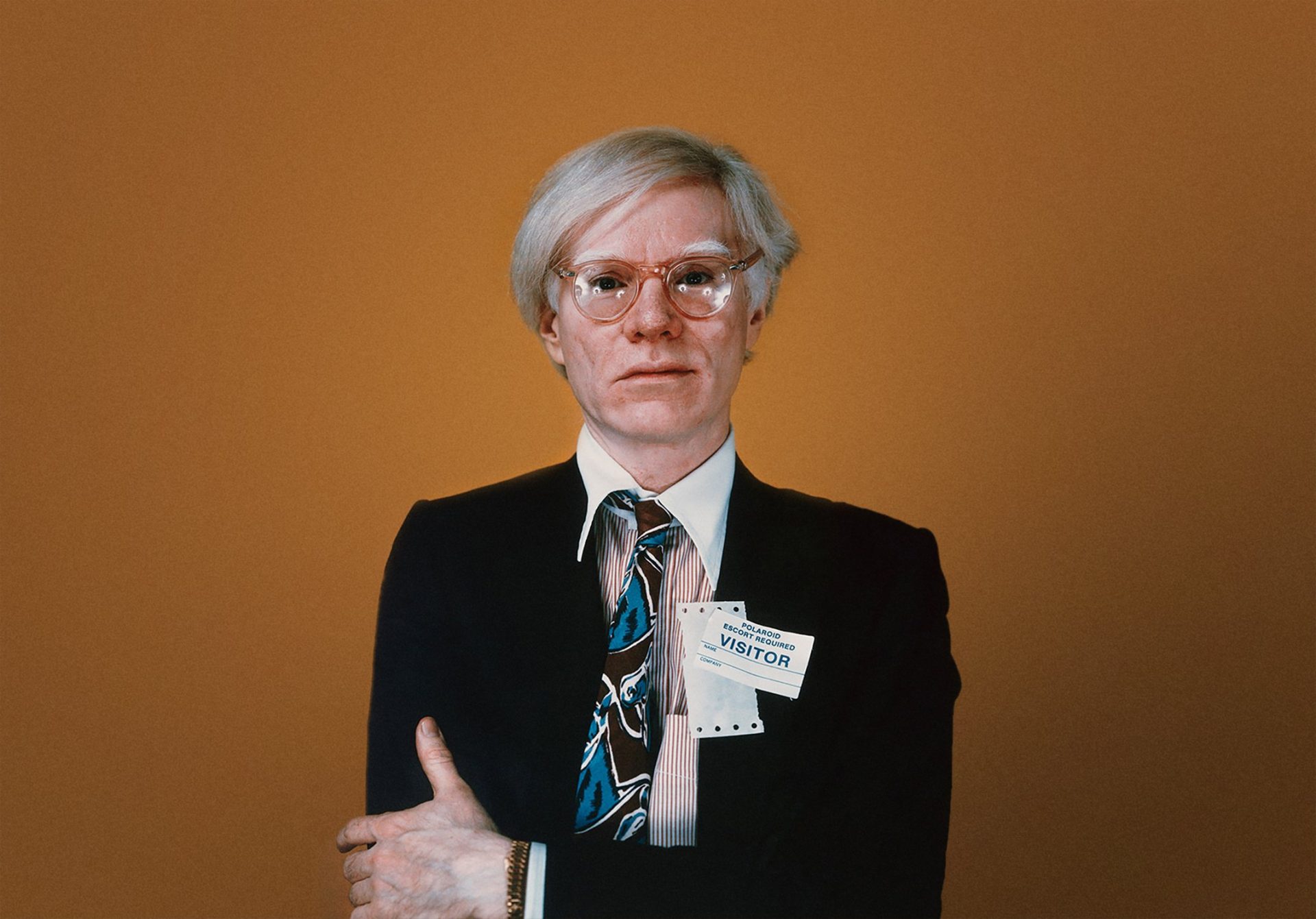

A portrait taken of Warhol wearing a gold Rolex, courtesy of Art Image.

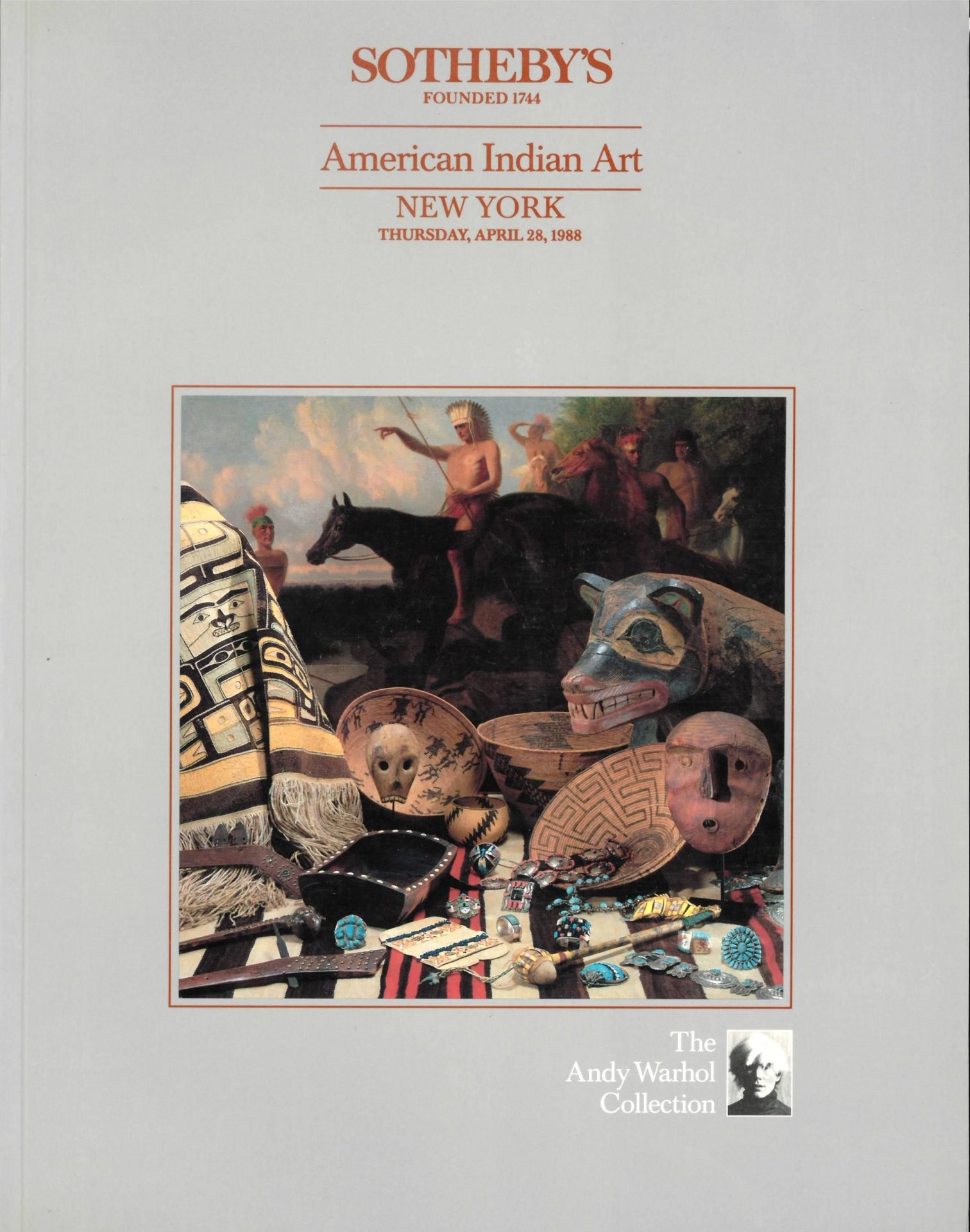

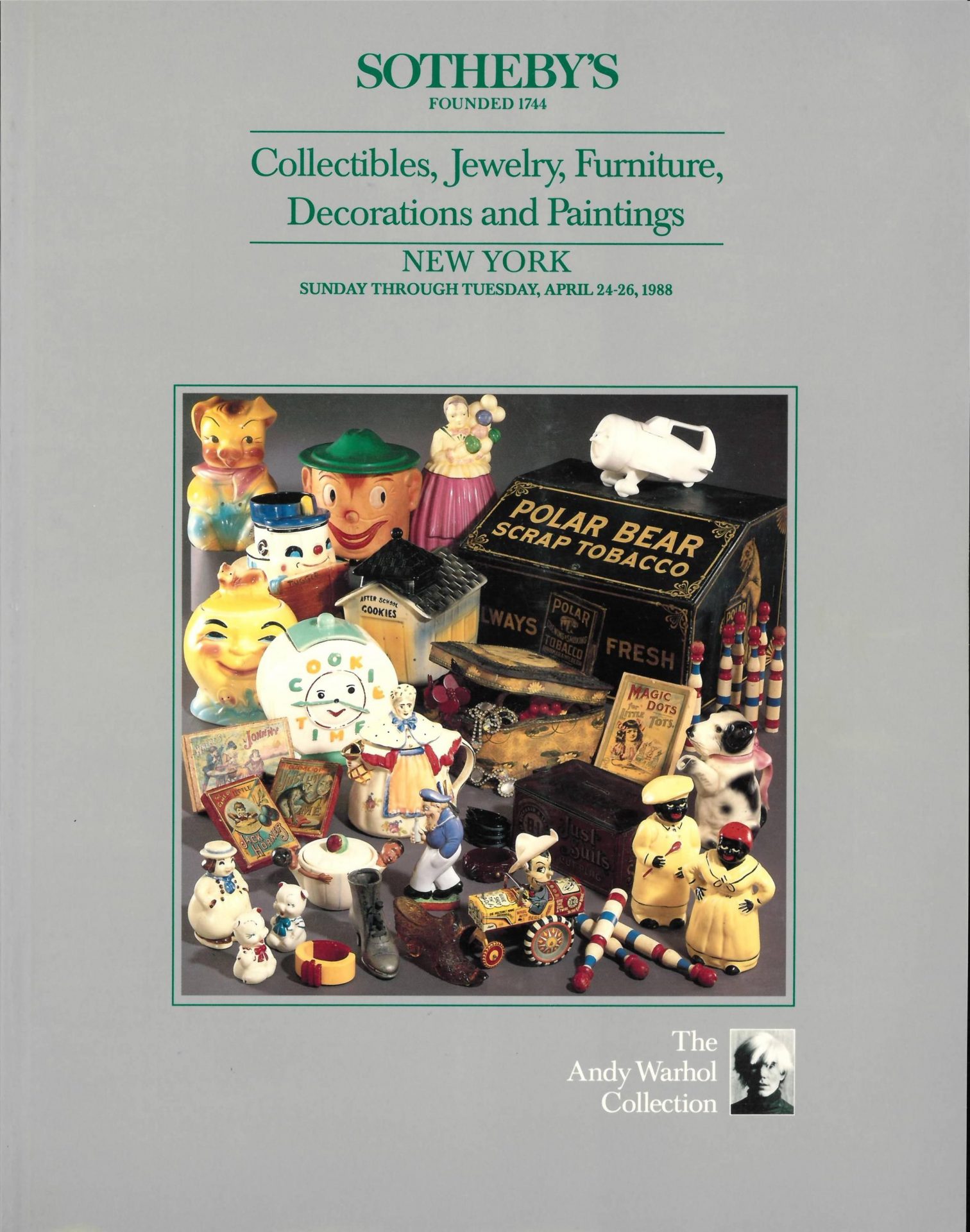

Outside of his horological fascination, Warhol amassed incredible amounts of art, furniture, oddities, and curiosities. So much so that when Sotheby’s listed everything for sale, in aid of the Andy Warhol Foundation, it took them days to sell it all. His tastes were not restricted by the art he produced either, with pieces spanning across Modern art, Art Nouveau and Art Deco, even including Native American art and textiles. Perhaps some of the most curious additions were items like kitsch cookie jars and cigar store Indians. The only common thread that perhaps links all these together is Warhol’s appreciation for them.

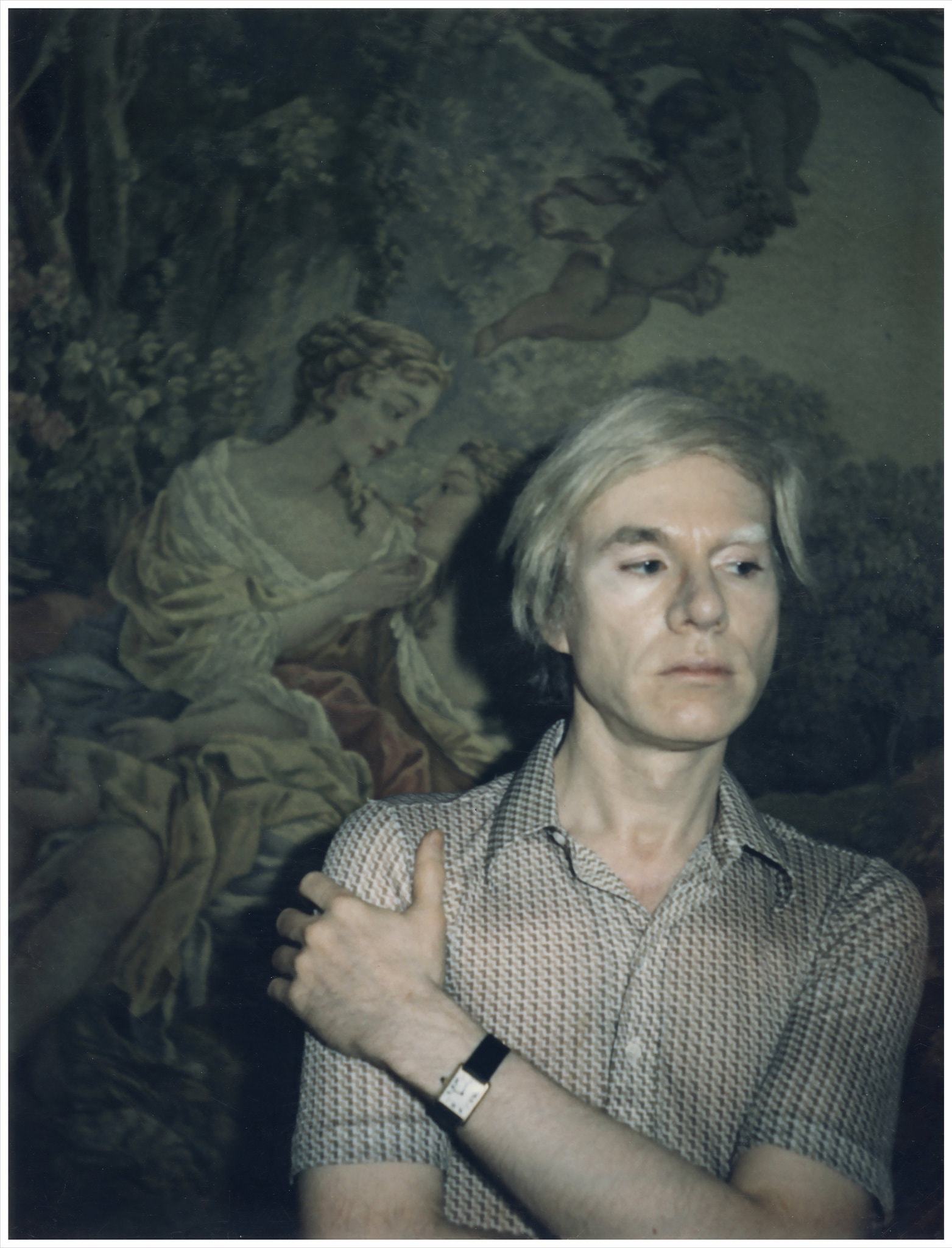

To get a better understanding of them, we wanted to speak to those with first-hand experience of Warhol and his collecting. This includes Todd Levin, an art advisor who worked with the silver haired artist from the 1970s onwards, and Daryn Schnipper, who was involved in the sale of his estate at Sotheby’s.

The Collector’s Mindset

It’s well documented that Warhol was passionate about a lot of things and as soon as he had the means, he indulged himself in acquiring all that he could. It wasn’t always the case of finding the very best example or the rarest variation. Warhol was more interested in curating a certain aesthetic and surrounding himself with objects that he admired. Warhol’s approach comes across as rather refreshing, with an unrestrained willingness to explore new areas and carve multiple paths of his own.

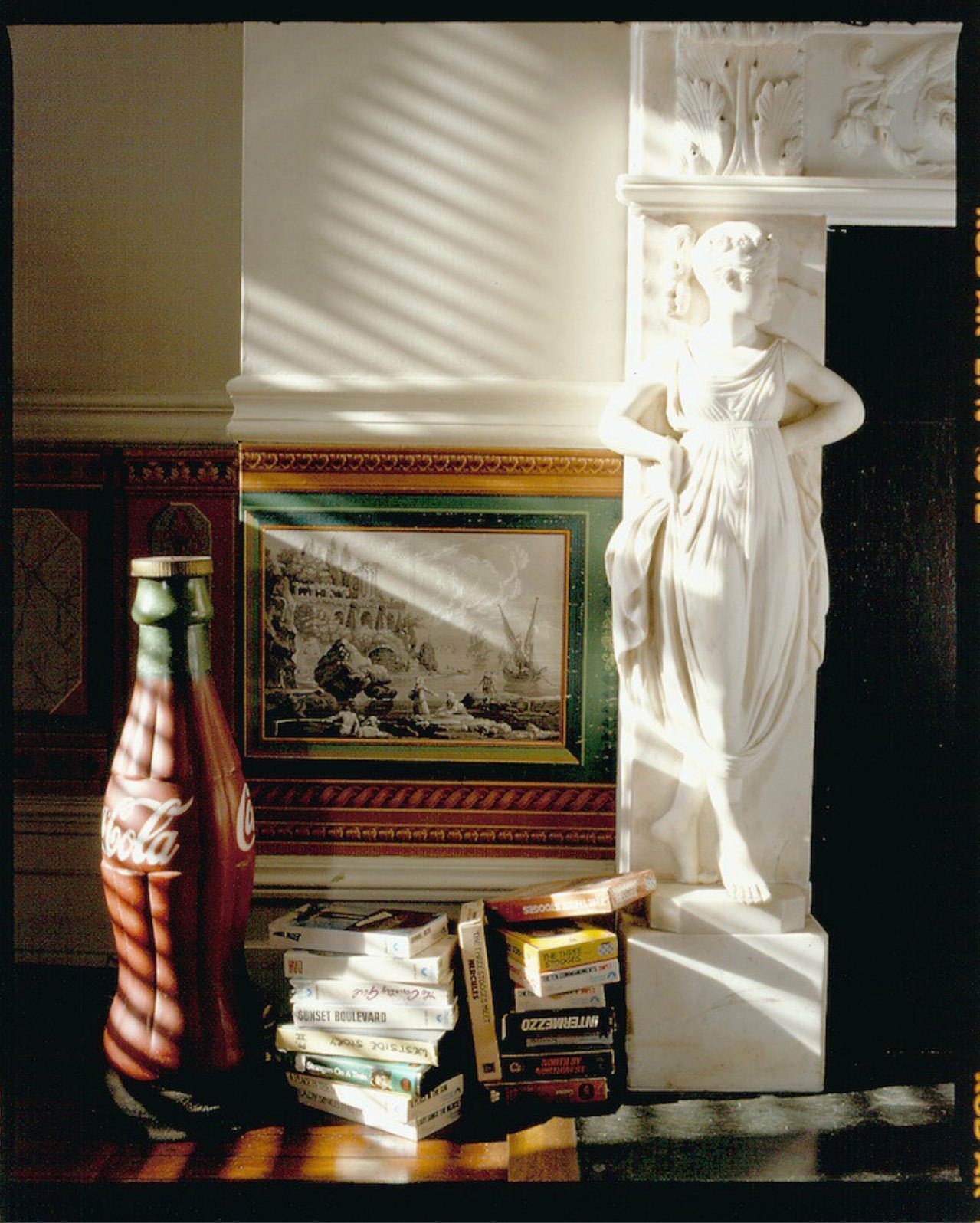

Two shots from inside Warhol’s house taken after he died taken by David Gamble and commissioned by Sotheby’s to help publicise his estate sale.

Not only did his collecting fill his massive New York townhouse – so much so that he apparently only lived in a couple of rooms – but anyone lucky enough to get a full tour at the Factory, his studio, would have noticed the various bits of furniture filling multiple corners. Even the screening room was kitted out with 12 vintage chairs of his choosing.

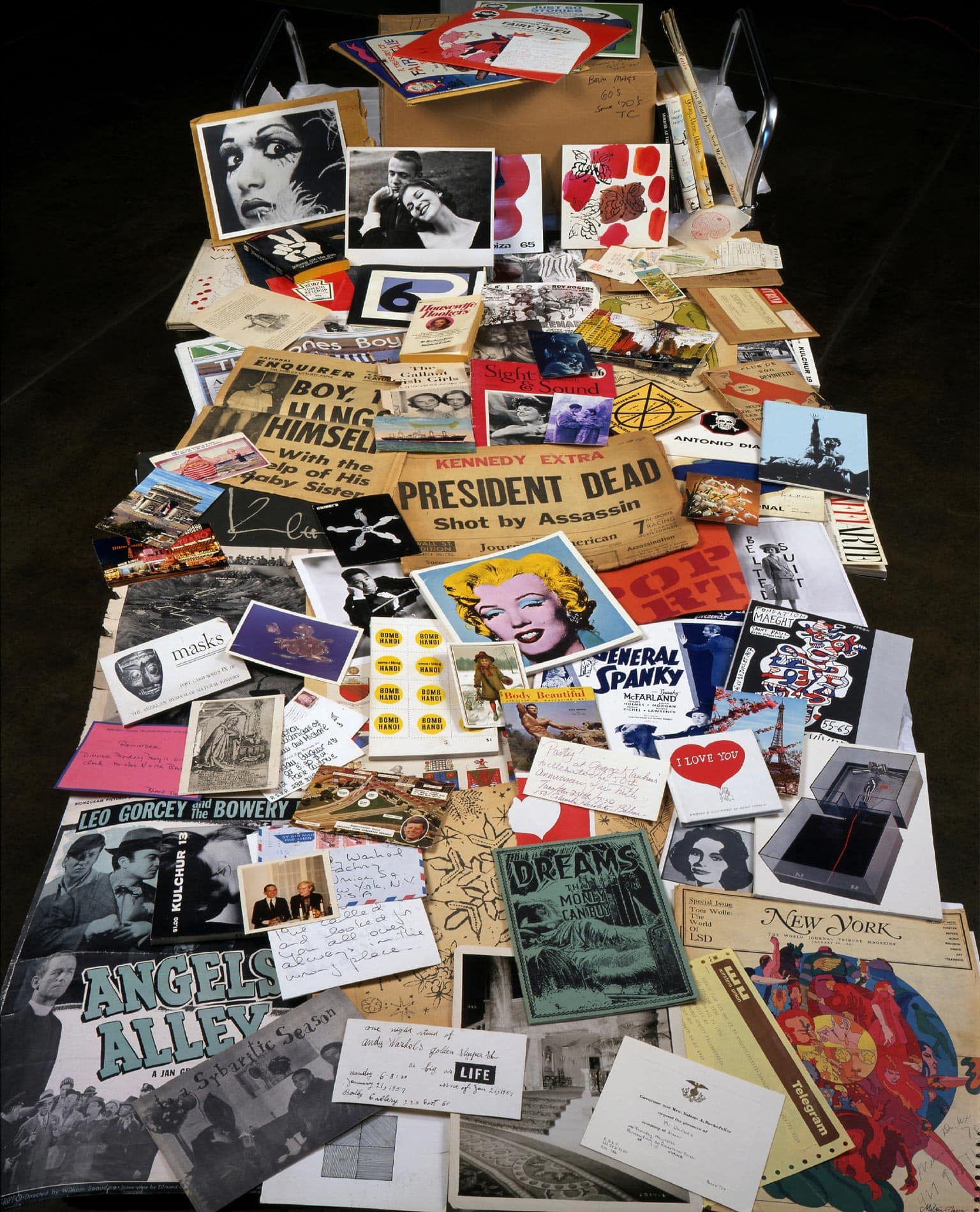

Perhaps the collection that best offers a glimpse into Warhol’s mindset were his time capsules. Every month, he would open a new plain brown cardboard box, filling it with different scraps of ephemera that he encountered every day over the next four weeks. This included everything: takeout menus, letters from other artists, labels, and anything else that crossed his path. At the end of the month, it was taped up, labelled, and put into storage.

A wall of boxes containing Andy Warhol’s time capsules in the Andy Warhol Museum, courtesy of ID Magazine.

These boxes are now owned by the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, . This has offered us one of the most comprehensive studies of Warhol as a collector, allowing us to see what he thought was necessary to keep and to piece together, one scrap of paper at a time.

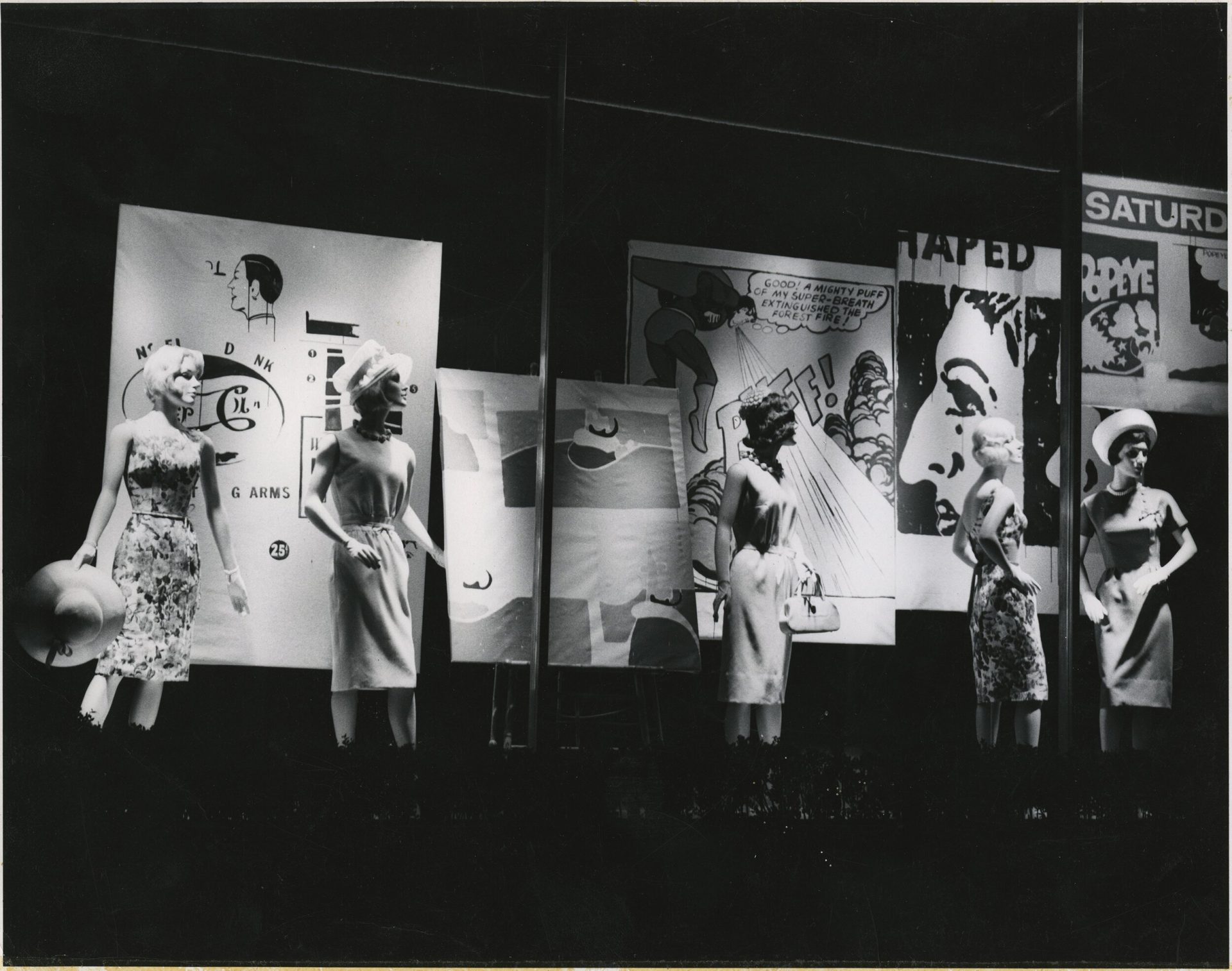

Speaking with veteran art advisor, Todd Levin, who was first introduced to Warhol as a child through his mother’s art collecting, gave us an insight into how the artist’s collecting passion started. A clear line can be drawn from his beginnings in the professional world to the immense number of possessions he left behind. “You can trace part of his buying obsession back to the shop windows at Bonwit Teller,” he tells us. For those unaware of the now closed New York department store, it held a reputation for being one of the best shops in the city for many years. Because of that, its window displays were prime advertising real estate, in the days before television advertising really took over.

Everything that was found inside Warhol’s time capsule #21, courtesy of The Andy Warhol Museum.

The driving force behind the window displays at Bonwit Teller was Gene Moore. A designer in his own right, when he wasn’t dressing the displays himself, he was commissioning artists to create a unique display. According to Levin, Salvador Dalí put together an infamous one that included a bathtub full of water. Supposedly, when he became upset that the team at Bonwit Teller tried to alter the display, Dalí attempted to rip out the bathtub, but slipped and both him and the tub went straight through the glass window, spilling out onto 5th Avenue.

These artistic displays were incredibly attention-grabbing and something that Levin suggests Warhol would have been more than aware of growing up and when he first moved to New York to pursue commercial art. Creating a community of artists that he looked up to and surrounded by a level of consumerism that would’ve been out of his reach growing up in Pittsburgh, Levin believes this was one of the genesis points of Warhol’s collecting mindset. Warhol was eventually invited to create his own display at Bonwit Teller. According to Levin, Warhol once aptly noted that “department stores are a lot like museums.”

The window display that Warhol produced for Bonwit Teller in 1961, courtesy of Grace Museum.

Of course, this one-off piece in a department store window was not Warhol’s only foray into commercial art. His work for fashion brands and magazines in his early career has taken on a legendary status. This work immersed the artist in the consumerist world, and he quickly became recognised as someone whose creativity could help sell products. Not only was it his skill with a brush that helped him thrive in this commercial world, but his insight in marketing, Levin tells us, was “well ahead of its time.” Able to be a once-in-a-generation artist, avid collector, and savvy marketer placed Warhol in a category of his own.

Collecting began to consume his daily schedule only after he was well established on the scene and running his own studio — at first known as the Factory but later simply the Office — and after he had become the stalwart of the Pop art movement that we know him for today. According to Levin, he would spend his days with a friend travelling around New York “with a big stack of Interview magazines” looking for possible advertisers.

One of Warhol’s many storage spaces with an eclectic range of the objects that he managed to pick up, shot by David Gamble commissioned by Sotheby’s.

He would not aimlessly wander the city, but travelled to the biggest shops on Madison Avenue, all the auction houses, “big and small,” says Levin, and the flea markets. As he visited these places he would be constantly on the lookout for his next purchases. “His tastes would come in waves,” says Levin, “and he would be intensely buying during that time. He would go from buying anything he could find to do with Native American producers, to focusing on jewellery, and then on to Art Deco.” This almost became a full-time occupation for him at this established stage in his life.

While the reports of his house being stuffed full of objects are true, it’s important to remember that he wasn’t living like a hoarder or a kleptomaniac, Levin is keen to point out. “He had a big townhouse in New York, and he would start placing the things he’d bought on the far side of a room and would slowly fill it up, working his way towards the door until you practically couldn’t open the door. Then he would shut the room up and start on the next one. However, the rooms he lived in and used were kept in incredible condition.” While these descriptions can sound like he was drowning in possessions, it was far closer to an ordered chaos.

There was certainly still space to lean in Warhol’s house, courtesy of Watchonista.

While most collectors would recognise the need to let something go in order to buy the next object, Warhol was completely averse to the idea of selling anything. “There were stories,” says Levin, “of Andy consigning something to go up for auction, only to run back to the auction house later that day to pull it from the sale.” Even if he never saw these objects again, he clearly enjoyed knowing that he owned them.

“I don’t think he really prized anything above anything else,” Levin explains, “it was simply good enough that he enjoyed it and that made it desirable to him.” The very best example of this is his collection of kitsch cookie jars. With quantities reaching into the triple figures, these flea market buys became real stars of the estate sale that we will discover more about later. The possibility that some of these jars could have been stored next to – and prized just as highly as – a finely crafted piece of Art Deco furniture shows the varied mindset that Warhol brought to his purchasing.

The value that Warhol placed on objects was never tied to their price or usability. A classic example of this was the watch he famously sported, the Cartier Tank. In Warhol’s own words: “I don’t wear a Tank to tell the time. In fact, I never wind it. I wear a Tank because it’s the watch to wear.” Uninterested in how valuable or useful an object was, the aesthetic into which it fell, and how completely it did so, was far more important to him.

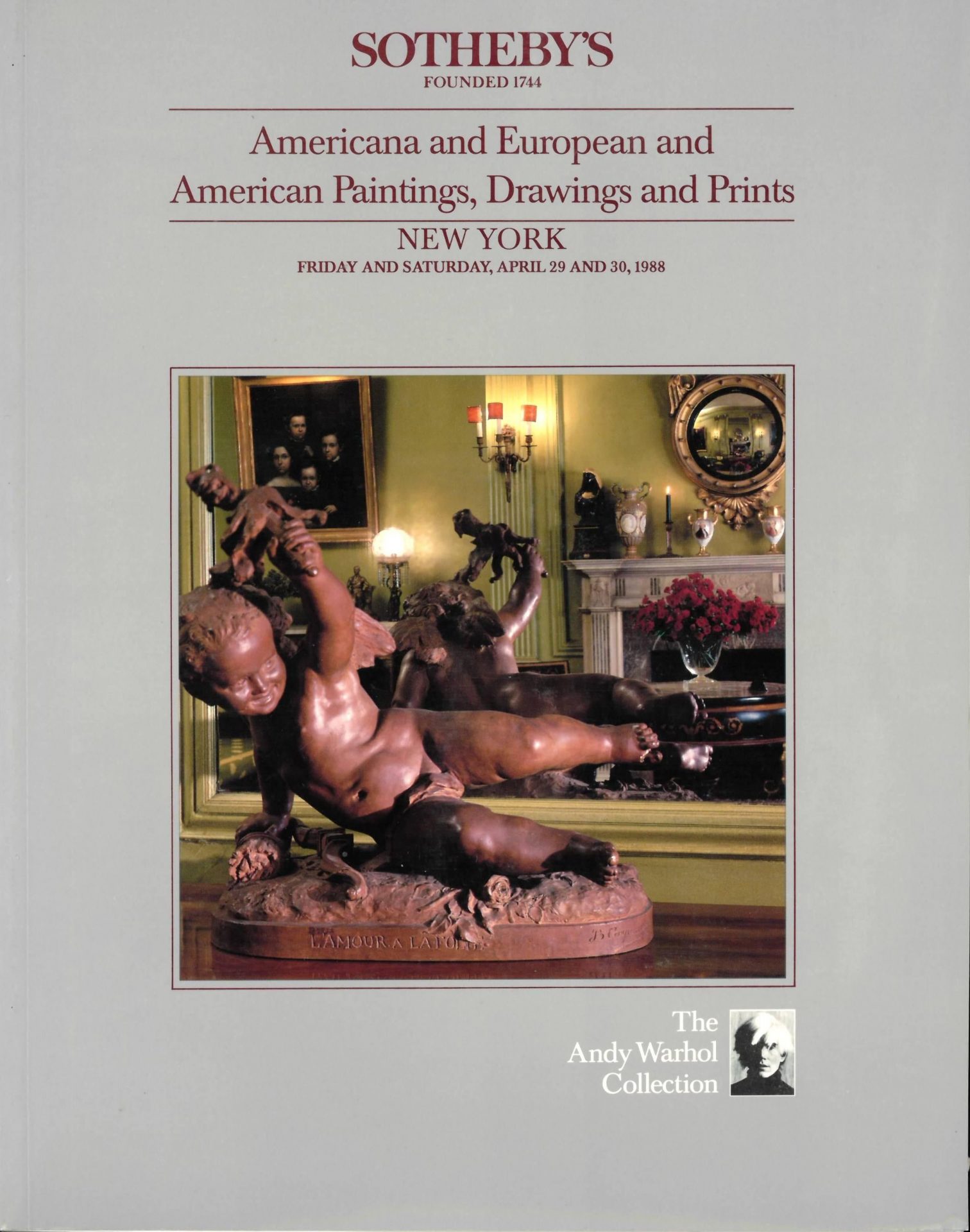

The Estate Sale

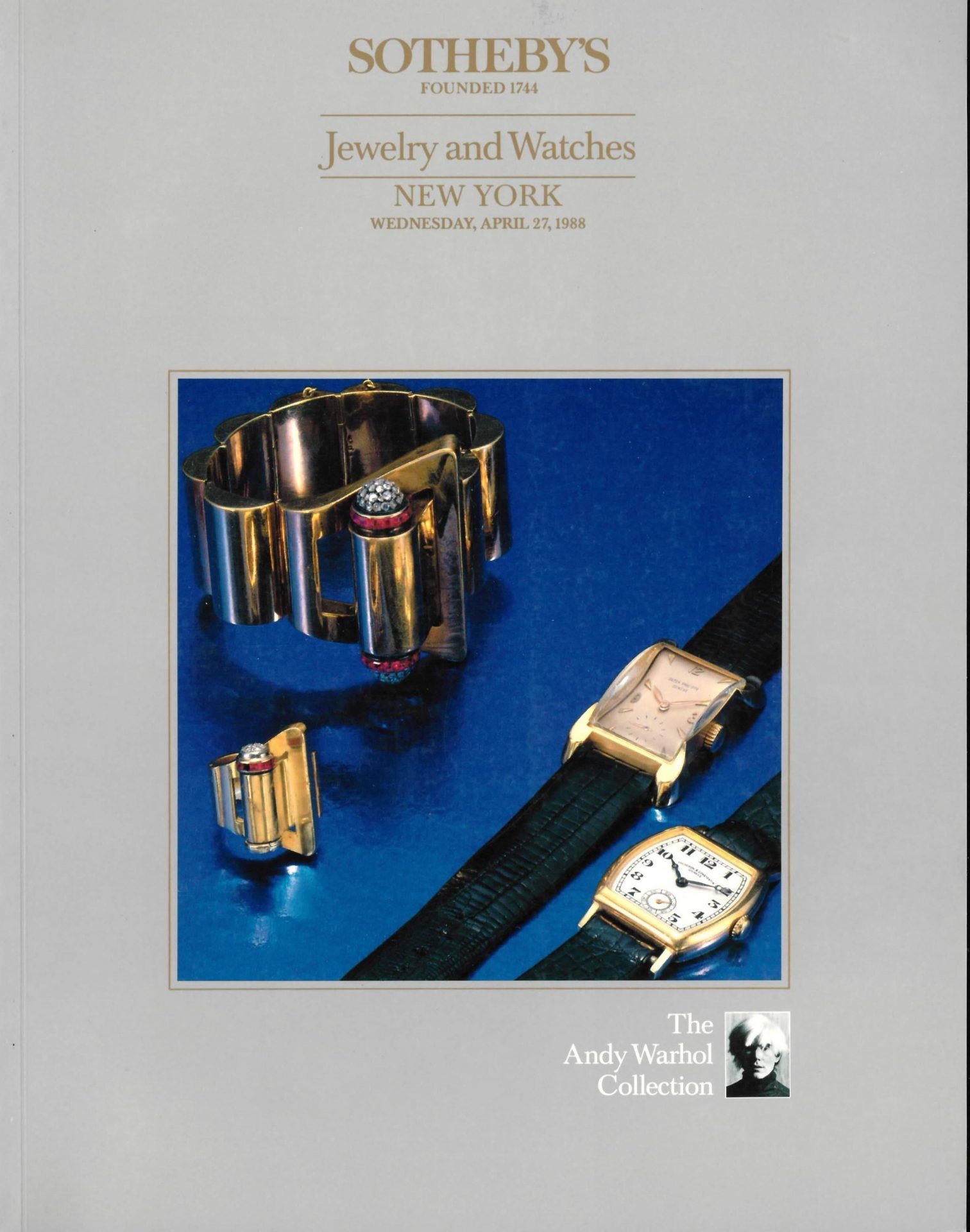

In 1988, after Warhol died from complications after gallbladder surgery, most of his possessions – of which it should be clear by now, there were many – were bequeathed to Sotheby’s to auction off, with the proceeds going to The Warhol Foundation. So plentiful was his estate that it took Sotheby’s 10 days’ worth of auctions to sell it all off. Levin told us that when collecting, Warhol had “an auction’s mindset”, in that he looked at objects as falling into certain categories, similar to the classifications that auction houses use when grouping certain objects together. This made Sotheby’s job fairly easy, by dividing everything up into specific sales. This meant that throughout the 10 days there were separate American Art, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Native American Art, Jewellery and Watches sales, and so on.

Four of the auction catalogues that were provided for the many sales that took place of the 10 days, courtesy of 1st Dibs.

“It was a whole thing,” Daryn Schnipper, Chairman of the International Watch Division at Sotheby’s told us, looking back on when she was the lead watch specialist for the sale. It gained such wide coverage that at the start of every day, “you could see people lined up down the street to get in. Even celebrities were queuing to get in.” Of course, Warhol was a very popular and present force in New York throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s. Thanks to his daily routine, which often took him out into the city, a lot of New Yorkers felt like they had a connection to him. Shopping at the same flea market that he did or picking up a copy of Interview magazine made people feel closer to him than they might with many public figures today.

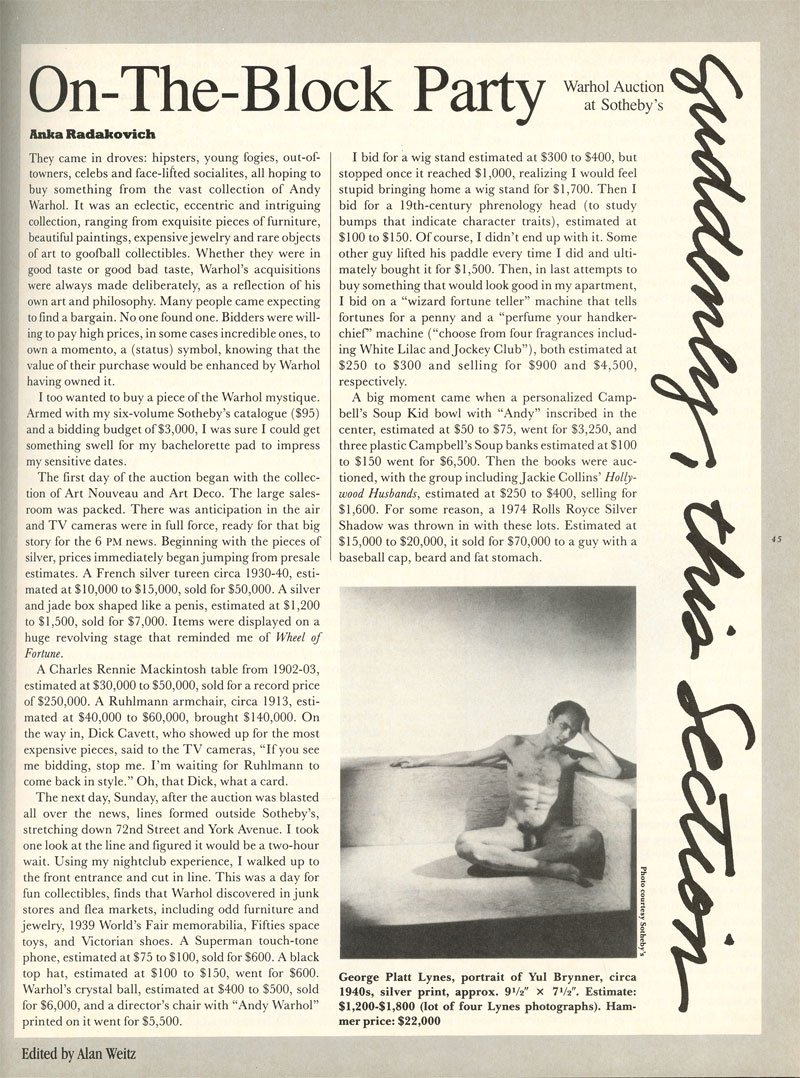

This familiarity that people felt with him drove the prices in these sales to new heights, as everyone wanted a piece of Warhol. “It was like a party scene,” Levin told us, who also attended the sale. “The evening sales of some of the bigger, more serious pieces of art were far more like a traditional auction, but the day sales of the objects were like a cross between an auction, a flea market and a party.” According to Schnipper, “our offices were on the third floor, and we had a box that looked out over the auction room, so when it wasn’t our sale, we were just able to watch and enjoy the spectacle.”

An article from Details magazine about the party-like atmosphere that surrounded the sale.

In order to get everything to the auction house, teams from Sotheby’s had to go in and find everything that had been left for the sale. Schnipper and her team were one of the first groups to go in. Some might remember that there was a watch and jewellery sale that took place as part of the main auction, but there was also a second one that happened months after. This wasn’t because there were more collections of watches and jewellery than anything else, rather it was because after everything had been cleared from the house, leaving only large pieces of furniture, a second stash of watches and jewellery was discovered.

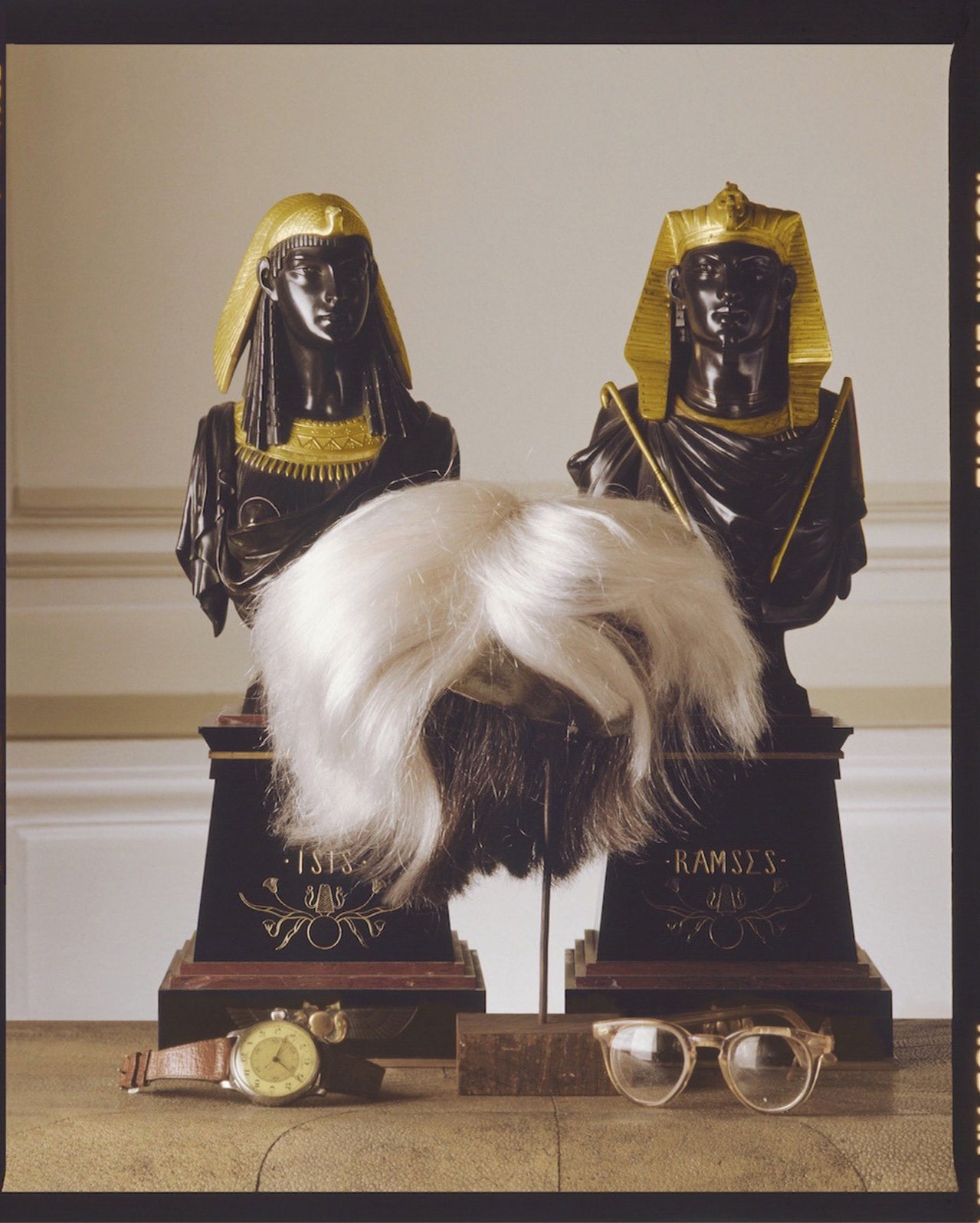

“We actually had a code name for this second collection, which was ‘Stash’, because of the way it was stored,” Schnipper tells us. “As the four-poster bed in Andy’s bedroom was being removed, this second collection was found in its canopy.” While the first sale had about 160 watches, this second sale contained about 100 lots, just on its own. Not one for keeping his possessions in a safety deposit box, the storage of this hoard perhaps typified Warhol’s lifestyle.

A handful of the watches that were found in the ‘Stash’ and were put into the second sale, courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The prices that were achieved at this sale were previously unheard of. With serious watch collecting very much in its infancy at the time, it wasn’t thought that much would come of this particular sale, yet the prices were astounding. One piece that Schnipper remembers clearly was one of the last lots of the first sale, which was a small selection of plastic quartz wristwatches. She remembered walking through Bloomingdales a few days before and had seen the exact same watches in a display case going for $26 a piece, while the small collection owned by Warhol sold for $2,400.

For an even more dramatic example of prices becoming inflated during these 10 days, you only need look at his cookie jar collection. Levin remembers one bidder going aggressively after all of these individual lots, “it was so obvious that towards the final few pieces the prices went up and up as others just wanted to stop this one collector from monopolising the cookie jars.” The entire collection of 175 jars hammered for $250,000, although Sotheby’s initially expected them to bring in no more than $7,000. The one bidder who took home the majority of these items was Gedalio Grinberg, founder and chairman of the Movado Group.

Warhol reclining on the famous red sofa in the silver lined room in the Factory in 1967, Courtesy of the Andy Warhol Foundation.

However, this didn’t happen with everything that sold that day. While many talk of the “Warhol effect”, Levin would suggest that there was a limit to how far it could stretch. “When it came to some of the more serious pieces of artwork that Andy had collected, these were achieving more expected prices than the inflated ones we were witnessing from the day sales.” It’s thought that this was partly down to more serious collectors taking an interest in the artwork for its own merits, rather than because it was owned by Warhol.

This limitation was not restricted to the artwork, as a few of the watches followed a similar trajectory. One piece that Schnipper remembers was a Patek Philippe 3448. A rare watch, even today, it was estimated at $15,000 to $20,000, and achieved $22,000, including buyer premium. For the time, Schnipper concedes that the estimate they placed on the watch was in the lower end, so hammering at $22,000 was perhaps an accurate representation of where the market for this perpetual calendar stood. According to Schnipper, something that saddened her slightly was that there weren’t more true collectors bidding. However, the feeling was that they didn’t want to overpay for something just because Andy Warhol owned it. Clearly, provenance didn’t have as much pull as it now has.

Four of the watches that were owned by Warhol, sold in the original estate sale and have since found their way back to the market, courtesy of Christie’s.

While some did speak of the “Warhol effect”, it was certainly not an isolated incident. Levin remembers similar levels of willingness from bidders at the large sales of Jackie Kennedy Onassis. “An issue with personality driven sales is that people over bid and the price they paid will never be matched again,” Levin explains. He suggests that this is one reason why we hardly see any of these pieces coming back to auction today. Schnipper thinks that an additional factor is that many of those who were bidding at the estate sale were looking for a piece of Warhol memorabilia — they weren’t after something to collect and sell. This personality driven buying can be an incredibly powerful force. “People have even kept the sales tags from the auction,” Schnipper told us, “as we had one specially designed for it with an image of Andy on it.”

A collecting legacy

Warhol was a special artist, able to foster a cult of personality around himself whilst remaining surprisingly humble and down to earth. While we have spoken a lot about the objects that he accumulated, he was just as voracious in the people he collected and brought into his circle. His Interview magazine allowed him to not only promote those he saw as worthy of it, but also gave him a vehicle to meet those he hadn’t yet had the chance to.

Warhol wearing the watch he was perhaps most well-known for owning, the Cartier Tank, courtesy of The Andy Warhol Foundation.

The way he approached collecting wasn’t unique. There were certainly those who came before him that amassed similar – if not larger – collections. However, it was his independent ability to identify styles and his confidence to stick to what interested him that made him stand out. Just as his approach to art was driven by his previous life experiences, the way he went about collecting was a clear echo of his early life. While he will always be remembered as the brightest flame in the Pop Art world, his passion for collecting should never be forgotten.