Source: Images and content by A Collected Man @ ACollectedMan.com. See the original article here - https://www.acollectedman.com/blogs/journal/obsessions-design-marek-reichman

http://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0606/5325/articles/0005336-R1-24-25A.jpg?v=1628846030Leading the team that imagines every detail of Aston Martin’s creations, Marek Reichman’s role as Head of Creative for the famed British manufacturer is far-reaching. Traditionally, the brand has concentrated on their sports car offerings, whereas last year marked a sea-change for the 108-year-old company with the launch of the DBX, its first, and in many categories best-in-class, SUV.

Not that Reichman hasn’t worked on more practical projects before – he was responsible for last generation Range Rover, tackled the revamp of London’s Routemaster bus, and, trained as an industrial designer rather than an automotive one. It’s why he’s as likely to find inspiration in a hairdryer as anything on four wheels.

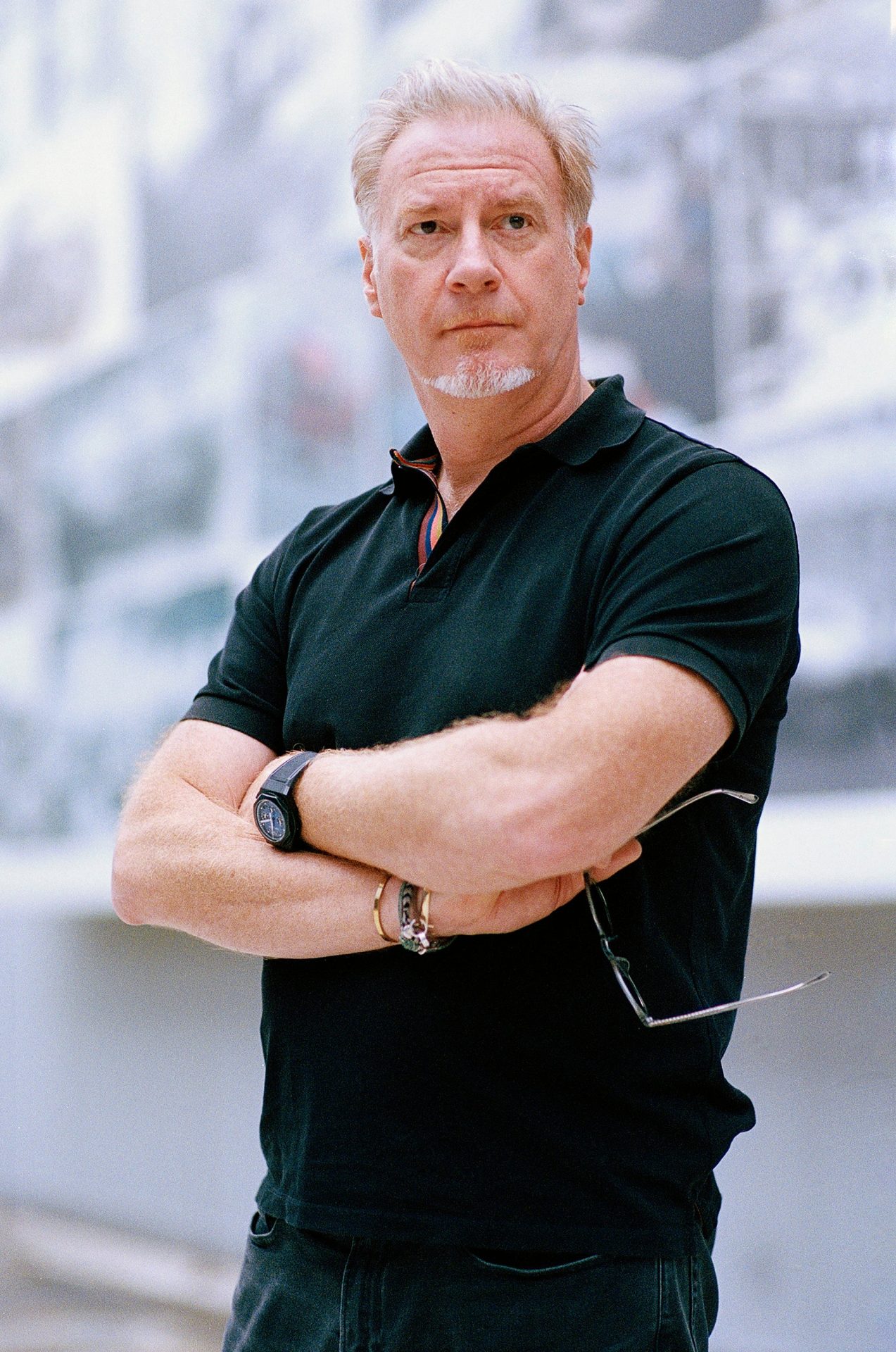

Reichman in his office at the Aston Martin Headquarters.

We sat down with Reichman to discuss his broad-ranging interests, tastes and work in the very heart of British automotive excellence, at Aston Martin’s headquarters in Gaydon. Surrounded by all of the usual ephemera that you would expect in the office of such a creative mind, from model cars to his eclectic and ever-changing mood board.

What’s your earliest memory of being excited by design?

I grew up in Sheffield, famous for the industrialisation of steel. My father was an artisan blacksmith, making chains for the QE2 and parts for Big Ben when it broke down. I have an older brother and together we were a bit of a boys’ club – his close friend was a mechanic and we’d go round to his garage where there were always these beautiful old cars he was working on. So, I was always interested in the processes of making things. And when my dad drove us around in his Vauxhall Victor – no seat belts then, of course – I got the whole wow for design in movement. I studied industrial design but always knew at the end of it that I wanted to design cars.

Reichman has come a long way from his childhood in Sheffield.

How does car design differ from industrial design more broadly?

It’s a matter of scale and emotion, though I think emotion is applied more to industrial design now than it used to be. Where industrial design pushes it pushes really to change something [about the way an object works or is perceived]. But the car hasn’t really changed since the early 1900s. We’re not levitating cars yet, so you need wheels, and you still have to seat the passengers.

But the emotional element in car design is huge. People fall in love with their cars. People have names for their cars in the way they don’t for their toasters. I hate to say it but your car is part of your family – it’s how you get to your friends, your work, get away on holiday maybe. It gives us freedom. Sure, we can get frustrated sat in them in a jam but – and I still do this – you might equally just go out for a drive. Not many people say ‘I’m just going to use my hair-dryer [for the pleasure of it]’, not to discredit the design of any hair-dryer.

What are the key parameters you have to keep in mind with a new car like the DBX?

Modern car designers are no longer just stylists, as we used to be called in the 70s and 80s. We’re fundamental to the process – we have to understand a new product’s place in the marketplace, target price, how it grows our customer base. Aston Martin customers have traditionally been 95% male – and an SUV changes that fundamentally. We actually created a female advisory board to make sure that, say, a 50th percentile Japanese woman can reach the pedals and see over the steering wheel. That’s hard with a sports car but we need to accommodate that with an SUV. You have to start thinking about how easy it is to get a baby seat in, because this is family car too.

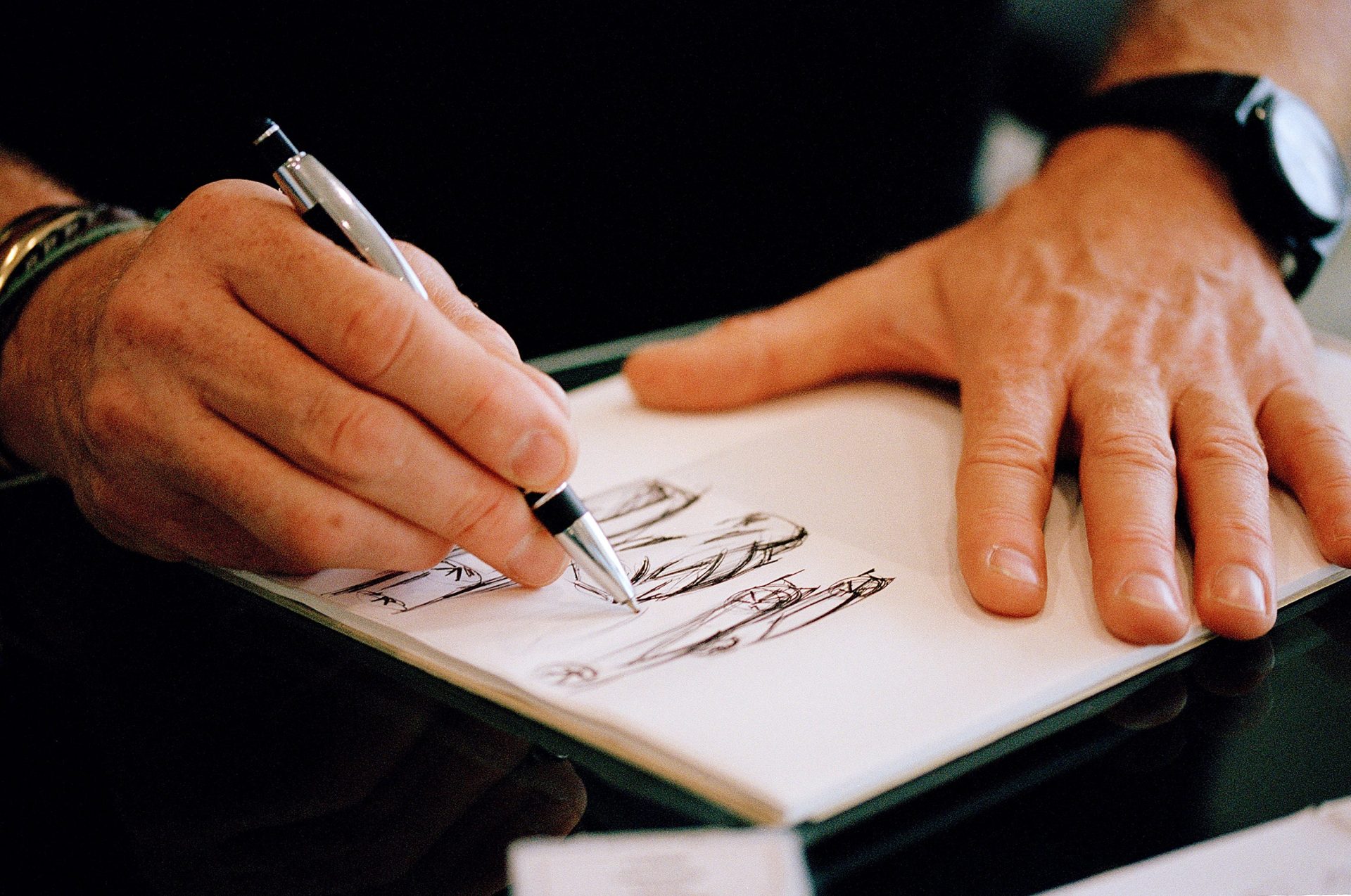

The basis of any car design has to start with an initial sketch.

Given Aston Martin’s desire to get more women driving its cars, do you think there’s any such thing as more ‘feminine‘ design, as some might claim?

No I don’t think there is. There’s a more feminine scale, of course. If you’re a small woman you’re grip is going to be smaller than mine, so if you then design [with just a man in mind] a steering wheel with certain thicknesses or angles or a particular offset to the centre console, then [anyone of much smaller stature] is just not going to feel comfortable. And if you don’t feel comfortable, if you feel intimated by the car, you don’t feel you can use it confidently.

You can likewise imagine a time when most GT cars will be a barrier to older people because they won’t be able to get their butts down low enough to get in or out. So design isn’t gender-specific but it is size- and age-specific. This is also where the advent of technology – warning systems, self-park systems – is really helping. Maybe you have a bad back and don’t have the agility to look back over your shoulder to reverse park. Well, cars can do that for you now. The more we have systems that take away physical restraints the better the design becomes.

“The emotional element in car design is huge. People fall in love with their cars. People have names for their cars in the way they don’t for their toasters…”

And then there’s getting the look of the car right, of course…

The visual language of something tells you about it and that’s key to what we do as designers. An SUV has to look as though it’s capable in more than just an on-road situation – and in fact, thanks to technology, the DBX does far more than its sporting looks suggest and is far more capable on the track than its more off-road looks suggest. It’s taking the ‘sports’ of SUV to heart, and why not, since our heritage is in making sports cars. But I wasn’t going to go through the ‘well you’ve designed a great looking car but you can’t fit in the back’ again. And I’m 6’4”. For me car design all starts with proportions, and then having the Aston Martin language, because I didn’t want it to be mistaken for anything else. That’s why it has the biggest grille we’ve ever done. Take the badge away and it has to unmistakably be an Aston Martin.

Just as it is watch design, proportions matter in the automotive world.

Speaking personally, what helps with the design process?

Travel is important, meeting people is really important, especially people in other creative fields. But music is really important to me – it’s a constant in the office and at home – because music creates moods and moods create forms, in your head. The music of the DBX saw a lot of Radiohead, a lot of Rolling Stones and New Order, because I’m a big electronic music fan, but also serenity, a lot of Bach and the cello. Different types of music can help you either bash out a series of quick exploratory design sketches or think about the last millimetre of a design. There are only so many notes. A tomato is a tomato. But a musician or chef have their ways of each doing something really different. And that’s the trick of the designer too – you have to apply your own methodology to come up with something different. Do I still get to use a pencil? Sure – though mostly in analyst meetings when I’m meant to listening…

How much push and pull is there between departments at Aston Martin?

There should be a push – the sales people should be behind every new car. They can’t design the car but they’re responsible for the relationship between the car and its new owners and so have to be part of the process. That’s important because part of what we’ve always marketed at Aston Martin is design. [As for me] it’s important to keep reminding myself what is an isn’t Aston Martin, otherwise you become complacent. Obviously there are a lot of traditionalists saying ‘no, Aston Martin should never do an SUV!’. But talk to, say, a millennial in China and she doesn’t know anything except SUVs. We have to respect where we were but my job is about the future – where we go next. The trick is to spread your language across [different] products. Sometimes you design a detail that you love but you also know isn’t right for the brand. Or you want to play with a brilliant idea that another brand really already ‘owns’. You just can’t do it.

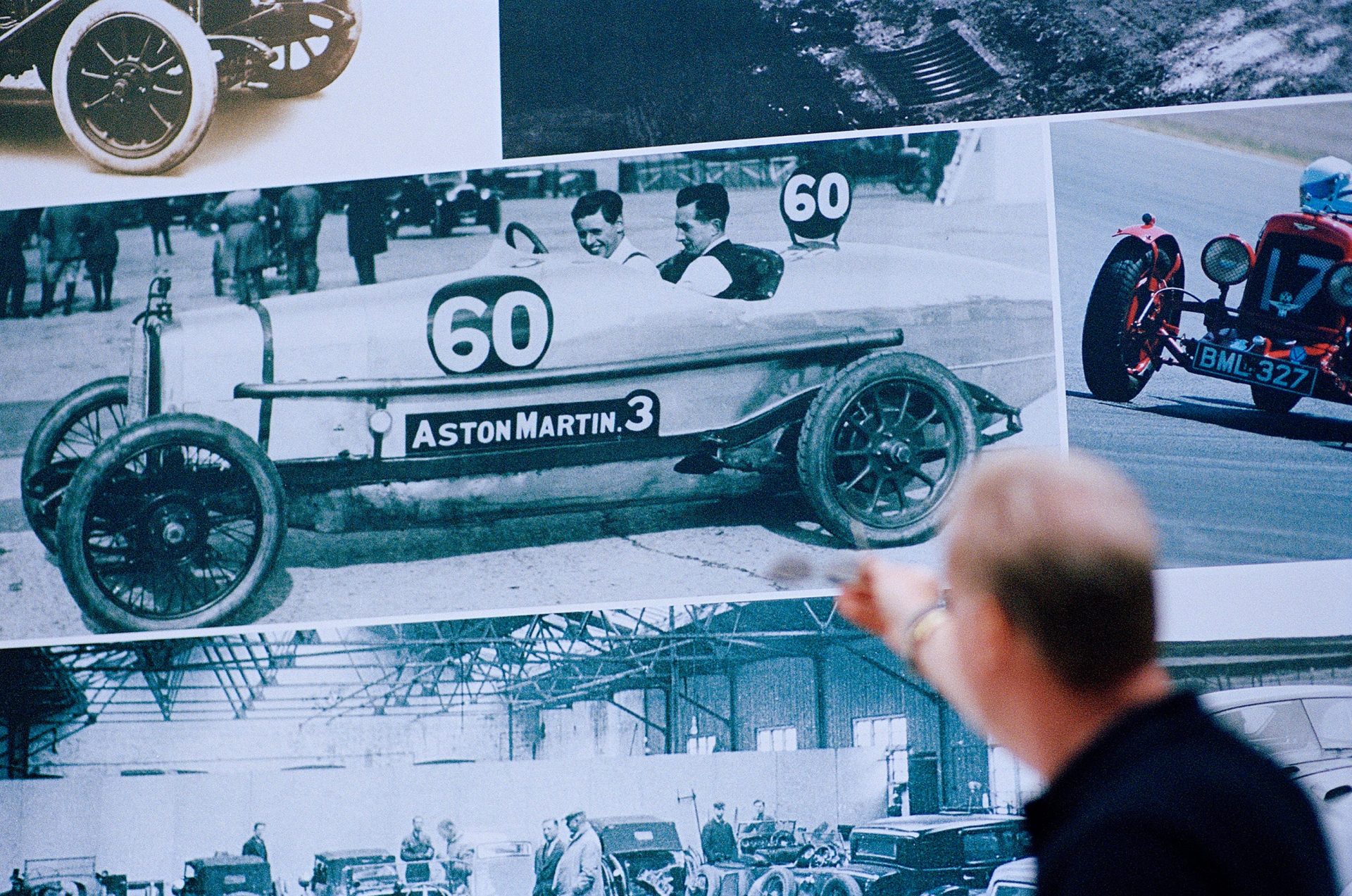

There is a lot of heritage that Reichman has to be mindful of in his role.

Aston Martin has often claimed that its one stand-out characteristic is beauty. But beauty can be boring. How do you keep the cars beautiful but interesting?

That’s where you have to keep pushing forward, and to accept that, initially at least, some people might not like what you do, where you’re challenging the norm. I think the Valkyrie [Aston Martin’s race car], for example, is an incredibly beautiful object, but it’s like an ant, an exo-skeleton, and certainly not everyone’s cup of tea. At the other end you might have the DB11, which is so much more tailored, more conservative. But even that has to evoke power. If I’m driving a DBS I often get people telling me that it’s not for them but still admiring how powerful it looks, the brutishness of it. You have to play with the norms of beauty, and you’re seeing that change in fashion and other disciplines too. You can find perfect function and perfect beauty [in the same object] but it’s not easy.

“Music is really important to me – it’s a constant in the office and at home – because music creates moods and moods create forms, in your head…”

Aston Martin is a ‘sexy’ brand and for you no doubt a good one to drop at a dinner party. But would you be just as excited designing, say, a transit van?

Yes, you have to be, otherwise don’t do it. With Norman Foster I won the TFL design for the new Routemaster bus and I didn’t sit down thinking ‘oh, I don’t really like buses’. I found out that the original Routemaster was created by the same engineers that developed the Lancaster bomber and that it had the same idea of using these rib-like structures with an aluminium core to give it strength. You soon get fascinated. You soon completely get into buses. There are certain vans I love. I’m a big fan of Series 1 Land Rovers, and the Willys Jeep, because they’re the ultimate in functionality. That’s exciting to me. I’d have loved to have been involved in designing something like the Defender.

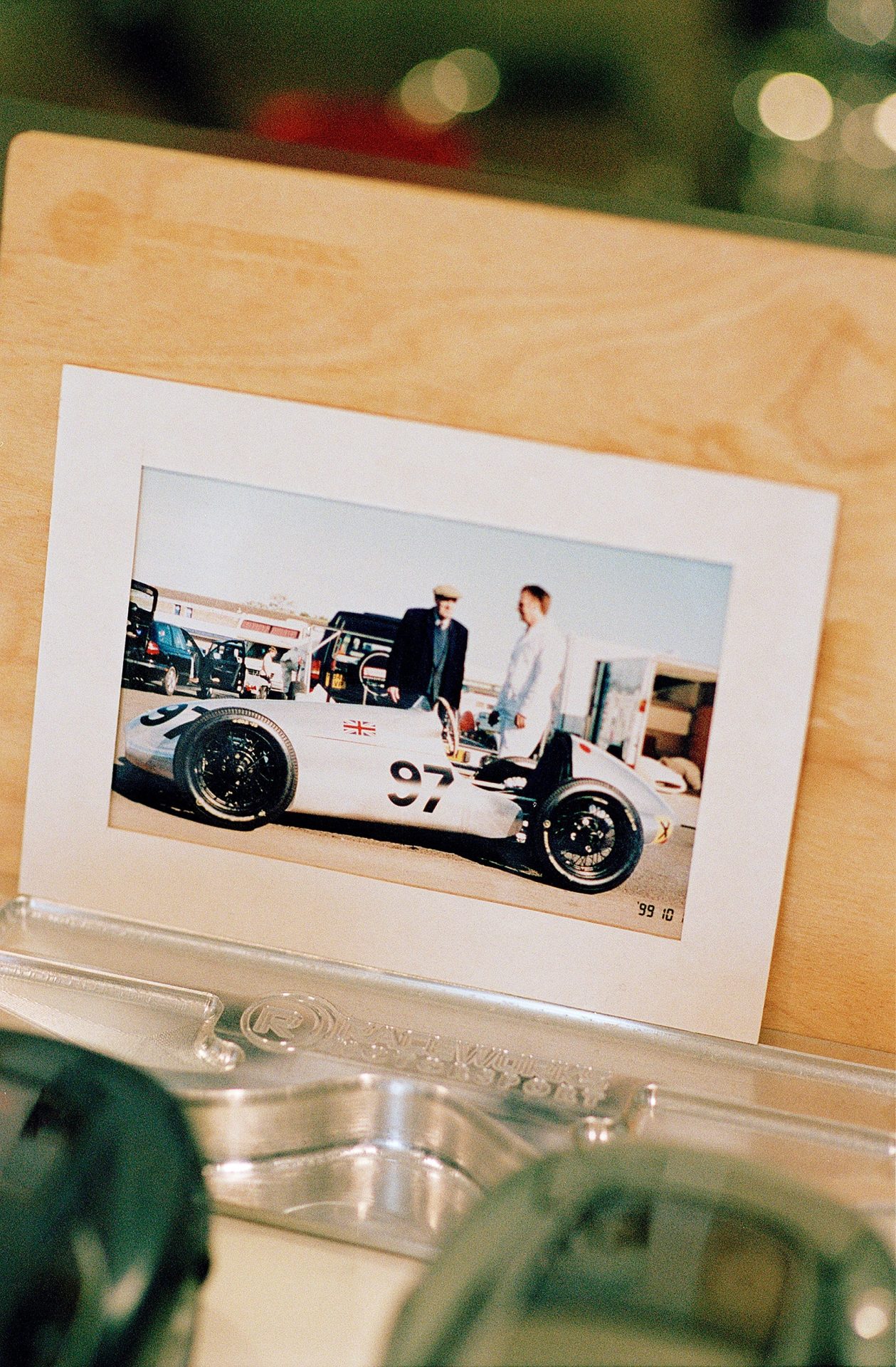

The vintage race car that Reichman has been known to take to the track in.

As the head of creative what leeway do you have in pushing the company to take risks?

Quite a lot I think, if you look at the differences [between the current Aston Martin models]. A new car can look nothing like the last generation but is still an Aston Martin. But this is also where the ‘specials’ we design are really important as they’re less risk [for the company], being a limited production run, but still sell-out instantly. You’re not having to rely on finding a lot of customers but they allow you to gauge what people may and may not like. We made just 10 DB10s for a James Bond movie, but it was a brilliant way to experiment with the visual language of our cars. And a powerful way too, because more people will have probably seen a DB10 than a DB11 given the eyeballs that Bond movies get. It’s an opportunity to be progressive and take people forward with us.

Has the Covid-related delay in the release of the next Bond movie been a big problem for Aston Martin?

Not really, because the film will come out eventually. We’ve got four cars in the next film so it does matter but it’s still going to happen. If they’d have said ‘it’s just not going to happen’ that would have been a disaster for us. The good thing about this movie is that there are a couple of Aston Martin cars that you can’t buy because they’re heritage products – or you can, in the sense that we’ve just done a DB5 Goldfinger Continuation but that will long be sold out by the time the film comes out – and then a DBS which has a lifecycle of another three or four years. The great thing about these movies is that people keep watching them, and watch them repeatedly. Someone might not realise it’s DBS the first time, but then do realise later.

The link between Aston Martin and the world’s most famous secret agent is as strong as ever, despite the long delay for the next instalment of the franchise.

What do you see as being the main challenges facing you as a car designer now?

The car world is changing fast. We’ve seen the rise of the likes of Tesla – a Silicon Valley company making cars, based not on automotive thinking but on Silicon Valley thinking. Connectivity is a big issue – think about the companies that are accelerating their reach in terms of what they do, how much data the likes of Google or Apple have about their consumers… We’re relatively novices in the car industry in terms of gathering customer data. Covid suggests that people are less likely to want to visit a dealership, so the Net-a-Porter way of selling may become more important.

How quickly can we update is also an interesting question – 10 years ago you replaced your phone maybe every 18 months and now for some it’s every four months. How does that affect car sales? Voice control systems 10 years ago were shocking too. Now they’re much better. The car industry is going to have to step up to all kinds of technological changes. Can cars make you healthier by reading your pulse or body language? Rather than reading a sign that suggests you take a break on a long drive, maybe the car will notice your pupils dilating and actually pull you in at a place of rest, for a coffee. And then there is electrification – the development of battery technology and the shift away from the combustion engine.

The practicalities of cars might be changing but the romanticism around them seems to be here to stay.

Given that, and given the practicality of the new DBX, do you think the pure sports car has any long-term future?

I think it does. There’s a group of consumers who will always want a sports car because it’s a toy, a gadget. Clearly, it’s limited compared with what an SUV can do but I’d cite the horse by way of comparison – in the 1800s people had horses to transport them, to plough the fields, to deliver everything. And then came the car. So now the horse is more for enjoyment, for riding, racing, jumping. But the point is that it’s still there, albeit for far fewer people. That’s going to be the case for the sports car, even if SUVs and practical cars will become more the norm. There’s still a passion and excitement for the most extreme versions of something. That fascination will always be there.

We would like to thank Marek Reichman for taking the time to speak with us and the Aston Martin team for helping to make this interview happen.